FORGIVENESS: A FRANCISCAN REFLECTION

By Evan Pederick tssf

A talk given to members of the Third Order, Society of St Francis

Hobart April 2022; evanpederick@gmail.com

____________________________________________________________________________

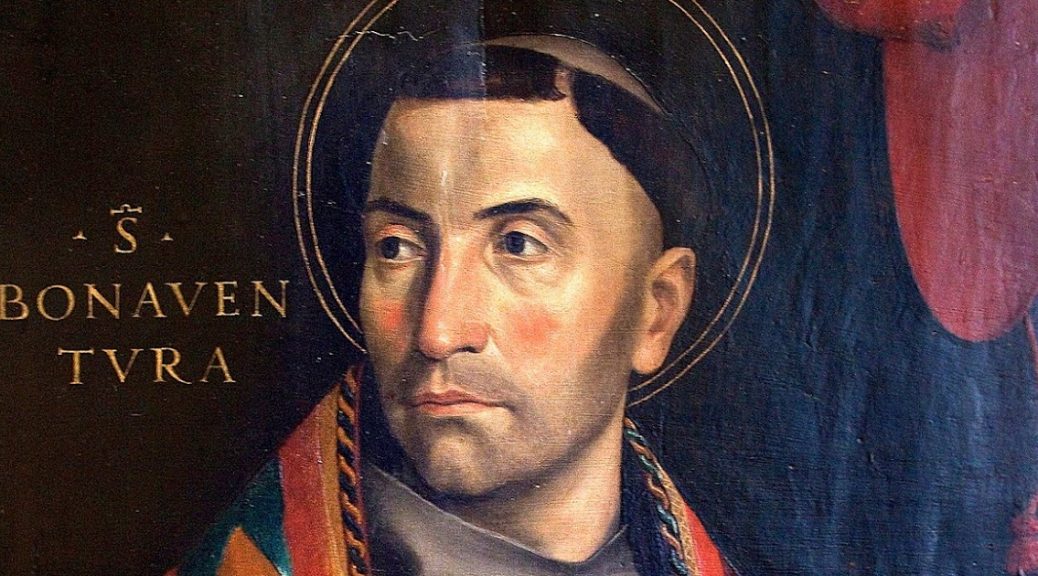

I decided to speak this afternoon about forgiveness when I noticed that the Gospel we will hear tomorrow, the third Sunday of Easter, teaches us about the connection between forgiveness and the way of resurrection. I want to start with this, Peter’s conversation with the risen Christ over breakfast on the shore of Lake Galilee, then develop some themes on forgiveness that run through the New Testament, before exploring Franciscan teaching on forgiveness through the stories told of the life of St Francis, his own teachings and finally the more systematic Franciscan reflection on forgiveness offered by St Bonaventure. As those who know my background will realise these reflections are deeply personal to me, and so I offer them as one who has been forgiven much but who has much still to learn about the way of forgiveness.

In the Fourth Gospel Jesus appears three times to his disciples following his conversation with Mary of Magdala in the garden of the new tomb on the morning of the first day. That same evening he appears to all the disciples apart from Thomas who have locked themselves away out of fear. The first thing Jesus says to his startled disciples is “Peace be with you”, in fact he says it twice in this short passage. It’s a standard greeting – but the Greek word eirene is also the equivalent of shalom in Hebrew, God’s original blessing and intention for creation. It is also – and this is worth remembering when we offer one another the sign of peace in church on Sundays – a blessing of forgiveness and reconciliation. So Jesus blesses them with shalom, breathing on them in a clear echo of the Genesis account of the first day of creation, and commissioning them for ministry: “If you forgive the sins of any they are forgiven; if you retain the sins of any they are retained”. Jesus is here inaugurating the Church as a community defined by the practice of forgiveness and love. The following week he appears to the disciples – with Thomas – and again pronounces the benediction of peace, blessing those who will come to believe even though they have not seen for themselves. The Church is now commissioned to be an agent of resurrection, to bring others to faith through its own ministry of forgiving love and by the power of the Holy Spirit.

The third resurrection appearance according to the Fourth Gospel is Jesus’ grilling of Peter over breakfast. Peter is carrying a burden of guilt so obvious that the Gospel writer doesn’t even bother to remind us of it: for each one of Peter’s increasingly desperate and self-serving denials in the courtyard of the High Priest Jesus asks him: “do you love me”? And for each one of Peter’s sorrowful replies Jesus instructs: “feed my sheep”. “Feed my lambs” (John 21.1-19). The primary purpose is not so much to make Peter squirm – although he does, and the unspoken fact of Peter’s load of guilt makes this uncomfortable reading for any of us who also recollect at this point our own failures of love and loyalty – but to confer forgiveness and with it a task. Jesus’ commissioning of Peter, and his prophecy of where in human terms Peter’s faithfulness will take him, underscore the point that while the free gift of God’s forgiveness has no strings attached our choice to receive it sets a new direction for our lives.

It’s the same point that Jesus makes in relation to the sinful woman who washes his feet in Luke 7.47: “she has been forgiven much: therefore she loves much”. Notice which way around it is? The divine initiative comes before our response is even possible. Jesus is pointing out that forgiveness reorients us to become the women and men God created us to be. In Luke’s most famous story about forgiveness, the story of the generous father of two sons – one profligate but broken and repentant, the other outwardly obedient but self-righteous and judgemental – the message is that divine forgiveness knows no limits but we need to be ready to accept it (15.11ff). For the profligate who knows his need of mercy, his father’s forgiveness is transforming and liberating – for the respectable son there seems to be a long way yet to go. In our Easter story, where Peter is stuck in his guilt and unforgiveness of himself, Jesus’ forgiveness and commissioning leads him from the death of self-loathing to new life. Where unforgiveness forecloses and kills, forgiveness opens us to new life and resurrection.

Jesus is big on forgiveness. In both Matthew and Luke’s versions of the Our Father Jesus connects our own forgiveness of others with God’s forgiveness of us. Matthew’s Jesus tells us to love our enemies and pray for those who hurt us (5.44). Luke goes even further: “love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you” (6.27). Well, but which comes first, you might ask – do we learn to forgive the difficult and unlovely because of our knowledge of how much we ourselves have been forgiven? Or are we somehow disconnected from God’s unlimited and unconditional forgiveness if we ourselves are unable to forgive others? What if forgiveness is so much a part of God that it surrounds us like the air we breathe – except our own unforgiveness shuts us in and keeps us from drawing breath? Others may point out that just saying the words, “I forgive you – or her or him – or even myself” doesn’t necessarily make it true, that maybe all we can do when the hurt has been too deep is just commit ourselves to wanting to forgive – that forgiveness needs to grow, it can’t be forced. And all of these observations are true, I believe. Forgiveness, like resurrection, is a path that leads to new and transformed life. But it’s not an easy path.

The most shocking example of forgiveness is Jesus’ own prayer on the cross which Luke tells us (23.34) he prays as his executioners hammer in the nails: “Father forgive them, they do not know what they are doing”. That seems to set the bar too high for us – many good Christians try to avoid it by saying, ‘oh, this is not Jesus forgiving his executioners personally, he is leaving it up to God’. But in the words uttered on the cross you and I are privileged to listen in on the intimacy of love that is the triune life of God. In his prayer on the cross Jesus is entering fully into the heart of forgiving love that is God – there is no separation between his own will and the will of the one he calls Abba. Neither, according to Luke, is this extreme of forgiveness even something that might be possible for God but surely could not be expected of us. In the second part of Luke’s Gospel – the Acts of the Apostles, Jesus’ shocking act of forgiveness is echoed on the lips of the first, exemplary Christian martyr, Stephen: “Lord, do not hold this sin against them” (7.60).

In relation to the stoning of Stephen, Luke shows us both a victim and a perpetrator, the young Saul who while not actually casting stones is a willing part of the lynch-mob and takes care of the attackers’ coats. Saul goes on to lead the violent persecution of the early Church: raiding the houses of believers, hauling believers off to prison and “breathing threats and murder” (Acts 8.1-3; 9.1, also Gal 1.13). New Testament scholars note the discrepancy between the irenic account in Acts and the defensive tone of Paul’s own letters that suggests his later ministry was not universally accepted. Certainly there seems to have been an ongoing tension between Paul and the Jerusalem apostles with whom he had no formal contact for 14 years following his conversion, as well as Peter whom he later accuses of hypocrisy.

Forgiveness transforms and gives new life, but the scars of sin remain. How could they not, when the risen Christ still bears the wounds of crucifixion? Paul works out his theology personally, and his vulnerability is on display in his letters. He acknowledges to the Galatians he had come to them “because of a physical infirmity” (4.13) and in 2 Corinthians writes of his ongoing struggle with a “thorn in the flesh” (12.7). These statements have been a thorny problem for centuries of New Testament scholars! They seem to be referring to the same thing, and the word translated in the NRSV as ‘infirmity’ (Gk astheneia) also appears a little later in the passage from 2 Corinthians. The Greek word sarx underlying ‘physical’ and ‘flesh’ in these two verses can mean physical in the modern sense (ie. bodily) but also carries the more general meaning of the mortal human state with its mixed needs and desires. On its own the Galatians passage could perhaps be read as Paul admitting ‘I came to you as a flawed human being’ but the 2 Corinthians passage suggests something deeper and more specific – at a human level Paul experiences himself as pierced or even ‘pinned down’. We don’t know the nature of Paul’s burden but perhaps he is referring to his own corrosive self-knowledge as a violent persecutor of the Church. Today we would identify this as ‘moral injury’.

Paul is certainly aware of his own unworthiness: referring to himself in 1 Corinthians shockingly as an abortion – the NRSV supplies the polite circumlocution lacking in the Greek – “as one untimely born …. unfit to be called an apostle” (1 Cor 15.9). In his magisterial volume on Paul, James Dunn comments in passing that Paul ‘for some reason not altogether clear to us’ avoids in his letters any direct discussion of the topic of forgiveness. Perhaps as Dunn suggests Paul simply prefers to emphasise not what he has turned away from but what he is called to. But Paul’s stunning theological conclusion is that his weakness is important because it reveals the sufficiency of God’s grace: “for power is made perfect in weakness … when I am weak, then I am strong” (2. Cor 12.9-10).

One of the dangers of thinking about our own practice of forgiveness is that we slip too easily into assuming it is about us forgiving others. This is one of the reasons the Church insists on the act of confession every Sunday before we can take together the bread and wine of Jesus’ risen life. And we have much to repent of, together. As a Church, for example, we too easily pass over our corporate sins of child sex abuse, or our historic role in the dispossession of Aboriginal Australians. Or our rejection of the ministry of women, or our tacit exclusion or lack of welcome of gay and lesbian Christians. As citizens of a wealthy country that imposes cruel policies on asylum seekers, that condemns unemployed Australians to live on a benefit calculated to be inadequate and that fails to address the social sin of homelessness – we are complicit through our silence and our failure to protest.

And this is all before we even lift the corner of the veil and peer into the murk of our own personal moral conduct. What do you need forgiveness for? Or to put it another way, what is the benchmark of conduct that does impress Jesus? The obvious answer is in the uncomfortable little parable of the sheep and the goats in Matthew 25 (v.31ff). Sheila, Matthew and Dennis Linn in their marvellous little book, Good Goats tell of a group of nuns studying this passage. “Well?”, the study group leader asked, “put up your hands. Which of you have ever given food to someone who was hungry? Or clothing to someone who was cold? Or visited someone in prison or in hospital?” Slowly, the hands all went up. “Congratulations!”, she beamed. “You’re all sheep!” But then: “well, but which of you have ever walked past a beggar in the street and not given them anything? Or not helped out at the soup kitchen when you could have? Or which of you have ever not visited that person in prison or hospital when really you could have? Even once?”. And the hands came slowly back up. “That’s not so good is it? You’re all goats”.

So, what’s Jesus going to make of us? Let’s face it, we’re all sheepish goats. Good thing the judge in this story is big on forgiveness!

We Franciscans often shake our heads at St Francis who frankly does seem just a bit too radical, too literal in his interpretation of poverty and discipleship. We love him, and his recognition that at the heart of everything is Christ, and his understanding that we are brothers and sisters with everything in creation because we all come from the same heavenly Father. But he does seem a bit extreme sometimes, doesn’t he?

In relation to forgiveness, Francis typically wants to put the fox in charge of the hen-house. There are a couple of stories which I’m taking from the 13th century work, The Little Flowers of Saint Francis, by Br Ugolino. And the first story is the rather famous one about the wolf of Gubbio – a wolf who, being rather elderly, had started preying on the livestock and even the people themselves, of the little Italian village of Gubbio. Legend has it that Francis, ignoring their concern for his safety, went out to remonstrate with the wolf. It crept up to him and put out its paw as if asking for forgiveness. Addressing the wolf as Frate Lupo (Brother Wolf), Francis told the animal that its behaviour was wicked and must stop. But, he said, I know that you are only doing it because you are hungry, and a wolf must eat. So he led the wolf back into the village and made a deal. The wolf would stop eating livestock and villagers, and in return the villagers would feed it every day, enough for its needs. Thereafter wolf and villagers lived in peace for about two years until the wolf died of old age. According to a recent biographer, in 1872 the skeleton of a large wolf was in fact dug up in Gubbio outside the chapel of San Francesco della Pace.

Leaving aside the (possible) historicity of the legend, the story is also directed at persons of a ‘wolfish’ nature who nevertheless may also be persons in need. Also in the Flowers we find another suspiciously similar story. In this one Francis visits a Franciscan hermitage that is being harassed by robbers living in the forest who have been terrorising visitors and coming to the hermitage demanding food. On learning that the robbers had been sent away from their latest raid empty-handed, Francis demanded that the guardian of the hermitage, Br Angelo, go after the robbers with food and wine and ask their forgiveness for his hardness of heart. After eating of the bread of charity, so the story goes, and witnessing the repentance of Br Angelo, the robbers sought out St Francis who admitted them forthwith to the Order.

This story is also recounted by the 19th century Franciscan friar, Fr Pamfilo da Magliano, who places it directly after the story of the wolf of Gubbio and significantly also gives to the robber threatening the hermitage the name of ‘Lupo’. According to da Magliano it is Francis who tames the human Frate Lupo with ‘a few gentle words, such as had perhaps never been addressed to him since he lay in his mother’s arms’. The point which da Magliano’s creative editing clarifies is that even wolfish behaviour may stem from deep human needs and that perpetrators too may be victims. Forgiveness must come with concern for the boundaries and practical needs of both parties.

It is in the Admonitions of St. Francis that we see the saint’s practical and pastoral yet most challenging teaching. The Admonitions also relieve us of any idea that the early Franciscan community was peaceful and perfect! In many of these short teachings Francis directly addresses the challenges of forgiveness, with its related themes of humility and peace: for example in his teaching on self-control he cautions friars against blaming others for their own sin – these days we would call that projection, when we react with offence at others who seem to be acting out what we deny in ourselves. Before we cast blame on others we always need to examine and ask forgiveness for ourselves. In the admonition against anger Francis points out that our anger at other people almost always covers our own sinfulness! Avoid sin, Francis teaches, by investigating what makes you angry. In his discussion of this teaching, John Talbot acknowledges the place for righteous anger but points out (from ps. 4) that it too must come from a heart of stillness. Control of our emotions is never easy but it is specifically forgiveness that cures anger. Forgiveness sets both us and those around us free from sin. By contrast, judgement sets like cement, locking us up in anger and not allowing others the possibility of change.

In his admonition on correction, Francis instructs his friars to bear correction from others as patiently as if it was from themselves, even if it is for something they didn’t do! Friars should be always willing to be corrected without making excuses. In our self-entitled age this is so much harder than it looks! And as for cheerfully accepting undeserved blame – but the point is that the spirit of true forgiveness is not about getting the recognition we deserve or credit for doing well, but about real humility which as men and women created out of dust is the only right attitude for disciples who want to grow in love. The word humility, incidentally, comes from the same root as humus, good compost-y soil. It’s not a way of saying we are worthless, but points us to an eco-spirituality of knowing ourselves not as self-sufficient individuals but as part of the more-than-human ecology of creation.

By the time of St. Francis’ death in 1226, the Order he founded had begun to tear itself apart. With thousands of friars across Europe, the Order had bogged down in a mess of administrative problems including institutional needs for finance, education and formation. Even worse, Francis’s own legacy and rule of life was bitterly contested. The so-called “spirituals” insisted on an ever-stricter interpretation of Francis’ rule of poverty, and inspired by the sensationalist 12th century apocalyptic vision of Joachim of Fiore proclaimed Francis as the angelic harbinger of a great cosmic conflict, setting aside both Old and New Testaments and ushering in the end of time. The seventh Minister-General, the brilliant and pious St. Bonaventure inherited in 1257 a sadly divided Order riven by mutual excommunications and condemnations.

Factionalism and loss of unity in a community of faith is nothing less than a turning away from resurrection. If we are no longer seeking unity we are no longer, strictly speaking, the Church. This is also a sad reality for us today. Bonaventure would prove himself an able administrator and peacemaker, establishing a narrative about Francis that was able to unite the warring factions as the Order continued to grow apart from the radical vision of its itinerant founders. I have previously suggested that his major work of spiritual theology, the Itinerarium Mentis in Deum, written in the first two years of Bonaventure’s installation as Minister-General, was a major step in crafting a unifying institutional spirituality suitable for a no-longer itinerant and marginalised community. A close reading of the text also reveals that it is constructed as a via pacis, or handbook of practical reconciliation. In this work Bonaventure invites his reader to inwardly retrace the steps of Francis and to be re-formed in the image of Francis as a person of peace, prayer and contemplation oriented to the image of Christ crucified. Bonaventure’s interpretation of Francis in the Itinerarium develops a theology of peace culminating in the penultimate event of Francis’ life, namely the reception of the stigmata. Bonaventure scholar Jay Hammond points out that the spiritual exercises of the Itinerarium are constructed so as to guide the contemplative friar through and beyond both outer and inner landscapes through the reconciliation of opposites led by the persona of Francis himself. In doing so, Bonaventure sympathetically reframes and incorporates the apocalyptic theology of the “spirituals” into his interpretation of Francis and particularly the meaning of the stigmata. Here the way of reconciliation is practically conceived as that of prayer, and in particular the reorientation of the images of our own minds into a focus on the ultimately unifying image of the crucified Christ. Bonaventure understands that practical reconciliation in the community of faith can never come about through the winning of arguments, or by decree, but only by fixing our gaze together on the one who in his death and resurrection embraces and collapses all our partial truths and contradictions.

Bonaventure’s formal theology of forgiveness is helpfully teased out from a variety of sources by Theodore Koehler. Bonaventure’s primary theological methodology is the metaphysic of exemplarity – meaning that he builds on the Christian neo-Platonism of St Augustine – and this leads him to see Christ as the Exemplar and Image of divine Love, the cosmic centre and coincidentia oppositorum or paradoxical union of the opposites of eternity and creation. Bonaventure begins the historical Franciscan theological emphasis on the primacy of Christ, which is to say that the Incarnation of divine love is the reason for and the ground and culmination of creation itself. As Richard Rohr expresses it, ‘everything in creation is an example, manifestation and illustration of God in space and time’. What this means is that the divine intention for the whole of creation is to be gathered together into Christ in the triunity of divine love.

As creatures made in the image of the Exemplar of divine love our human vocation is to imitate Christ. In relation to mercy and forgiveness Bonaventure discerns three movements which in God’s triune life are indistinguishable (but in our case need a little extra work). Firstly is the distinction between mercy (misericordia) and justice (justitia). While divine justice is conceived by Bonaventure as the ‘proper application of divine goodness’, mercy is the love and compassion that arises viscerally (per viscera misericodiae Dei nostri) – through the divine bowels, or as Bonaventure more delicately interprets it, the womb of God. In other words mercy arises when we are affected by the wretchedness of another and respond out of pity. Glossing Psalm 25.10, Bonaventure writes that mercy and justice are indistinguishable in the divine life, and that in human life mercy completes justice because both must find their appropriate balance. As an example of the indistinguishable operation of divine mercy and justice we might consider the parable of the vine (John 15.1-5): “He removes every branch in me that bears no fruit. Every branch that bears fruit he prunes”. Divine mercy comes with necessary limitation! In human life Bonaventure distinguishes between giving alms because it is right (justice) or because we are moved by another’s misery (mercy).

The third divine attribute for our imitation is piety (pietas). The Latin word connoting the duty owed to those with whom we share a blood relationship is defined by Bonaventure as a gift (donum pietas) of the Holy Spirit by which we see in another the image of God. Whereas mercy looks at the misery in a fellow human creature, piety looks at the image of God in the one who is wretched. This is Bonaventure at his most Franciscan: we recognise our own kinship with the other as a child of God, and even more importantly we recognise the crucified Christ in the face of the one who suffers or is alienated by sin. Mercy and forgiveness that is based in piety is an identification both with the creature who is made in the divine image, and with the suffering God who is found in solidarity with all who suffer.

With this observation, Bonaventure takes us back to the beginning of our reflection. Forgiveness draws us together into the heart of God. Where at the outset I claimed forgiveness as the practice of resurrection, we end with a model of deep forgiveness as creation participating in the triune life of God.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

References

Br Ugolino. The Little Flowers of St. Francis of Assisi. New York: Heritage Press, 1930.

Da Magliano, Pamfilo. The Life of Saint Francis of Assisi and a Sketch of the Franciscan Order. Kindle Facsimile. New York: P. O’Shea, 1867.

Delio, Ilia. Simply Bonaventure: An Introduction to His Life, Thought and Writings. New York, NY: New City Press, 2001.

Dunn, James D. G. The Theology of Paul the Apostle. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 1998.

Hammond, Jay M. “A Historical Analysis of the Concept of Peace in Bonaventure’s Itinerarium Mentis in Deum.” Saint Louis University, 1998.

House, Adrian. Francis of Assisi. New Jersey: HiddenSpring, 2001.

Koehler, Théodore A. “The Language of St. Bonaventure and St. Thomas: A Study of Their Vocabulary on Mercy.” Marian Library Studies 29, no. 29 (2010): 11–24.

Linn, Dennis, Sheila Fabricant Linn, and Matthew Linn. Good Goats: Healing Our Image of God. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1994.

Pederick, Evan. “St Bonaventure’s Itinerarium as a Bridge: From Francis to the Franciscans.” Third Order, Society of St Francis (blog), August 28, 2021. https://tssf.org.au/2021/08/.

Rohr, Richard. “Christ Is the Template for Creation.” Center for Action and Contemplation, 2018. https://cac.org/.

Talbot, John Michael. Francis of Assisi’s Sermon on the Mount: Lessons from the Admonitions. Kindle edn. Brewster, Massachusetts: Paraclete Press, 2019.