Francis Bernardoni was born in Assisi, Italy, in 1182. He grew up in a wealthy merchant family, received a basic education, and spent his youth partying. A war between Assisi and the neighbouring city state of Perugia saw him enlisting when he was about 20. After being wounded early in the battle, he was captured and imprisoned for many months, returning home weak and ill. Once rehabilitated he prepared to fight again, but along the way heard God’s voice in a dream instructing him to return home ‘and wait’. So began a long period of prayer and discernment, culminating in his renouncement of his father and all his possessions. Francis then adopted the lifestyle of an itinerant preacher, patterned on Jesus’ instructions to his disciples in Matthew chapter 10 where they are sent them out to preach the Gospel.

The townspeople’s initial ridicule soon turned to admiration, and a trickle of men – rich, poor, illiterate, academics – began to join him from Assisi and its surrounds. He accepted anyone who kept the faith, was willing to live in poverty, and obey his rule: before his death in 1226 an estimated 5- 6,000 “Little Brothers’ had taken up Francis’ song of praise and radical lifestyle across Europe, including England [1224], and the Holy Land [1217]. Pope Clement appointed the Friars ‘Custodians of the Holy Land’ in 1335, a position they retain to this day. Francis also founded a women’s order under Clare of Assisi, and a Third Order for people living in the broader community. Today there are both Roman Catholic and Anglican Franciscans, together numbering approximately 660,000 worldwide.

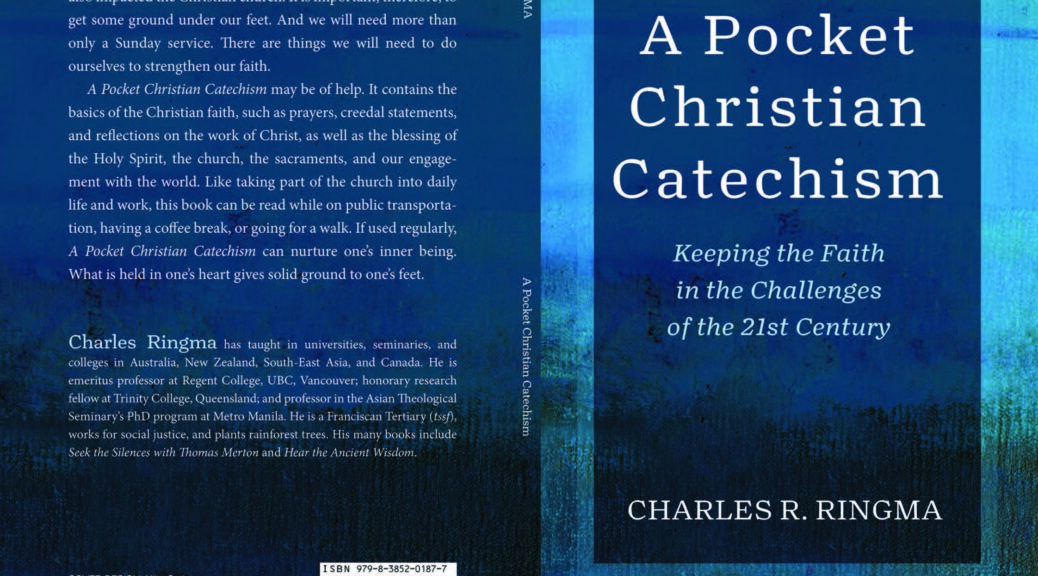

St Francis of Assisi captured my religious imagination

May the power of your love, Lord Christ,

fiery and sweet as honey,

so absorb our hearts

as to withdraw them from all that is under heaven.

So goes the Saint’s prayer ‘The Absorbeat’, concluding…

Grant that we may be ready to die for love of your love,

as you died for love of our love. Amen.

St. Francis was afire with love and passion for Jesus; his love was constant and unashamed: it absorbed his heart for sure, making him ready ‘to die for love of Jesus’ love’, as evidenced in his historical journey across the battlefield of the Fifth Crusade in Damietta, hoping for martyrdom. Whether he intended to convert Sultan al Kamil or to promote peace is contested; but it is known they parted on good terms and Francis’ writings from then on frequently refer to the value of peace-making, exhorting the Brothers to avoid quarrels and disputes. Following his namesake, Pope Francis met with Sheikh Ahmed el-Tayab, the Grand Iman of al Azhar in the United Arab Emirates in 2019: they signed a declaration of human fraternity and respect as a gesture of goodwill. It is said that the Saint’s promotion of ringing the Angelus bells trice daily across Europe encouraging the faithful to pause for prayer, was inspired by his experience of the adhan [Islamic Call to Prayer].

Early writings about St Francis and his first companions frequently refer to their infectious joy: it was Francis’ confidence and joy in God and transparent love for Jesus that reached across the centuries to draw me into his circle of influence like a magnet.

In the early 13th century God the Father was envisioned as fierce and intractable, whilst Jesus was frequently seen as the all-powerful and capricious judge, before whom folk quaked in fear. Francis revealed the true face of our compassionate Lord to a spiritually hungry people – and they responded in droves. There is nothing on this earth more attractive than genuine love and compassion.

The interconnection of all things

St Francis of Assisi has been dubbed the Patron Saint of the Environment, largely because of his legendary rapport with God’s feathered, scaled and four-legged creatures, illustrated in the oft-quoted stories of his interaction with them, such as the The Wolf at Gubbio, and Preaching to the Birds. However where contemporary solicitude for nature is largely generated from concerns for the prosperity and future of humanity, St Francis’ attitude arose from his devotion to God.

Eight hundred years before the word ‘ecology’ was coined, Francis understood the inter-connectedness and interdependence of all things intuitively. He called the elements, celestial bodies and creatures of earth, sea and sky ‘sister’ and ‘brother’, because of our common Creator. Scientists, such as Chris Impey, professor of astronomy at the University of Arizona, teach that ‘the carbon, nitrogen and oxygen atoms in our bodies, as well as atoms of all other heavy elements, were created in previous generations of stars over 4.5 billion years ago. Because humans and every other animal (as well as most of the matter on Earth) contain these elements, we are literally made of star stuff’. No doubt the writer of the Book of Genesis would be sympathetic to this theory.

Renouncing greed, St. Francis trod lightly on the earth, taking only what was needed to sustain life. Francis saw the Potter’s fingerprints on every created thing – and his reverence and love for everything under heaven was a natural extension of his adoration for their Maker. Fyodor Dostoyevsky eloquently encapsulates his attitude in the words of Father Zossima in his novel The Brothers Karamazov.

“Love all God’s creation, the whole and every grain of sand in it. Love every leaf, every ray of God’s light. Love the animals, love the plants; love everything. If you love everything, you will perceive the divine mystery in things. Once you perceive it, you will begin to comprehend it better every day. And you will come at last to love the whole world with an all-embracing love.”

Poverty/Simplicity

It’s impossible to speak about Francis or Clare without mentioning poverty. Francis chose “Lady Poverty’ as his bride and bound himself to her for life. Over a 40 year period Clare fought with successive Popes tooth and nail for the right for The Poor Ladies to enshrine total poverty as the basis of their life, finally gaining ‘the privilege of poverty’ a few days before her death.

A clear distinction needs to be drawn between what I term ‘imposed poverty’ -the grinding, soul-destroying suffering and deprivation accompanying those trapped in poverty by circumstances outside their control – and Franciscan or ‘chosen poverty’ -the free decision to follow Jesus’ example of leaving the riches of heaven, totally identifying with the poverty of human life and nature.

Franciscan poverty must also be understood as operating on both material and spiritual levels, encompassing the ongoing inner work of self-denial and humility and co-operating with the Holy Spirit in the transformation of one’s heart and soul.

‘Give to everyone who asks of you’ commanded the Lord Jesus, and the early Franciscans went as far as tearing off pieces of their habits if they had nothing else to give. Consider the desperation of a beggar who was grateful for a torn-off sleeve! The poverty and need in today’s world today also begs for relief, while rampant greed gobbles up natural resources and spews out toxins into air, waters and earth, wounding and infecting our sister Mother Earth, causing droughts, fires, famines and floods which toss the poor this way and that, starving and homeless…

‘Be doers of the word, and not hearers only…’ Thus St James [Chapter 1] exhorts his readers.

St Francis chose to refrain from lecturing others or entering politics: instead he simply lived the Gospel; providing a potent example of a life lived in solidarity with the poor, in imitation of Jesus. Actions, we are told, speak louder than words. His authoritative witness drew literally thousands of people to Christ, and continues to do so. Francis felt compelled to reach out to the voiceless, the rejected, and the needy. He embraced and assisted lepers and cared for the sick. He sent food to thieves. He befriended women, recognizing their abilities and intelligence. In sum, he endeavoured to follow Jesus in every particular.

Loving God disallows greed, selfishness and the pointing of the finger. Loving God leads us dancing with joy through life’s sorrows and sufferings with Francis and Clare into the abundant life of Jesus’ promise.

A significant mark of Franciscan spirituality is humility, which acknowledges that we can do nothing without God. All that we have and all that we are is gift – from the air we breathe to the earth upon which we walk. Only our sins are our own. This basic premise of humanity’s utter dependence on God was expressed through Francis’ reliance on God for every necessity and his cyclic lifestyle of withdrawal from and engagement with society. After drinking his fill of the Living Water, the Spirit drove him out into the world to serve the poor and preach the Gospel again. When he became empty and drained, back he went into a cave, up a deserted mountain – some quiet place – to spend time alone with God. Aware of his human frailty, Francis said: ‘I have been all things unholy. If God can work through me, he can work through anyone’.

Although the rest of the world ran after him, naming him a Saint; begging for his prayers and trying to touch him in hopes of a blessing, Francis made his share of mistakes: for example in accord with the prevailing understanding of holy living, he punished and neglected his body to excess, which contributed to an early death.

Prayer

Of paramount importance to holy living was prayer and nothing was permitted to usurp its primacy, indeed his life was saturated with prayer; however no ‘method’ of prayer can be attributed to St Francis as far as I know. The Eucharist held a central place: he approached the altar in reverence and awe, and wrote in a letter to his Brothers “Let the whole world tremble; let heaven exult when Christ, the Son of the Living God, is on the altar in the hands of the priest. O admirable height and stupendous condescension! O humble sublimity! O sublime humility! That the Lord of the universe, God and the Son of God, so humbles Himself that for our salvation He hides Himself under a morsel of bread.”

Apart from a meticulous observance of the Divine Office, he spent many solitary hours in the forest in deep contemplation, giving instructions that he was not to be disturbed, and at times during ordinary activities was known to be carried so deeply into prayer that he was unresponsive to this companions. Like many in earlier ages his memory was honed to a point virtually unseen these days, and large swathes of the Bible were committed to memory, upon which he meditated and pondered at all hours. Many accounts of St Francis’ intercessory prayer are recorded, and he made a habit of stopping what he was doing if approached by someone with a request for prayer, and praying then and there. St Francis was also know to pray using a mantra, as told by Bernard of Quintavalle, a wealthy man of Assisi who became Francis’ first follower. Bernard Inclined to join Francis, he wanted to be truly convinced that he was a holy man, and spied on him one night after he had invited Francis to stay with him. ‘Francis, who believed that Bernard was fast asleep, arose from his bed and began to pray with his eyes and arms raised toward heaven. Then, with great devotion, Francis began to pray aloud, “My God and my All!” And thus, with Bernard watching, Francis remained praying and weeping with great fervour until morning, repeating ‘My God and my All!’ and nothing more.’

Francis’ famous reservations regarding the pursuit of knowledge sprang, not from a lack of appreciation of intellectual excellence, but from a concern that study might displace prayer from its pivotal place in his Brother’s lives.

The Saint for our times

Our world, like the world in which St Francis lived, is largely ignorant of the true face of God. We are also surrounded by wars and violence, by corruption in society and [sadly] within the church. Many people have lost faith in the Church, and are wracked by spiritual hunger, mental anguish and anxiety. Depression amongst young people is a frightening thing –but understandable in the face of the mounting evidence of imminent climate crisis and misery looming in their future.

St Francis demonstrates the astonishing power inherent in living the Gospel; in actually believing and acting on Jesus’ teaching; in loving God with one’s whole heart, mind, soul and body; in utterly trusting the guidance of the Spirit, and in emulating the sacrificial love of Jesus the Christ whose redeeming love and mercy is inexhaustible. Franciscan spirituality then, is for ordinary people who recognise their imperfection and are aware that God’s light can shine through broken vessels.

Franciscan spirituality in short on prescriptive rules and long on love: in his parting words to his Brothers Francis said “I have done what was mine to do. May Christ teach you what is yours to do.”

God’s peace be with you.

Originally published on Roland Asby’s Living Water Blog, reproduced here by permission.