by Evan Pederick tssf, Perth WA, July 2021; evanpederick@gmail.com

Talk given to the Perth Third Order members

Abstract

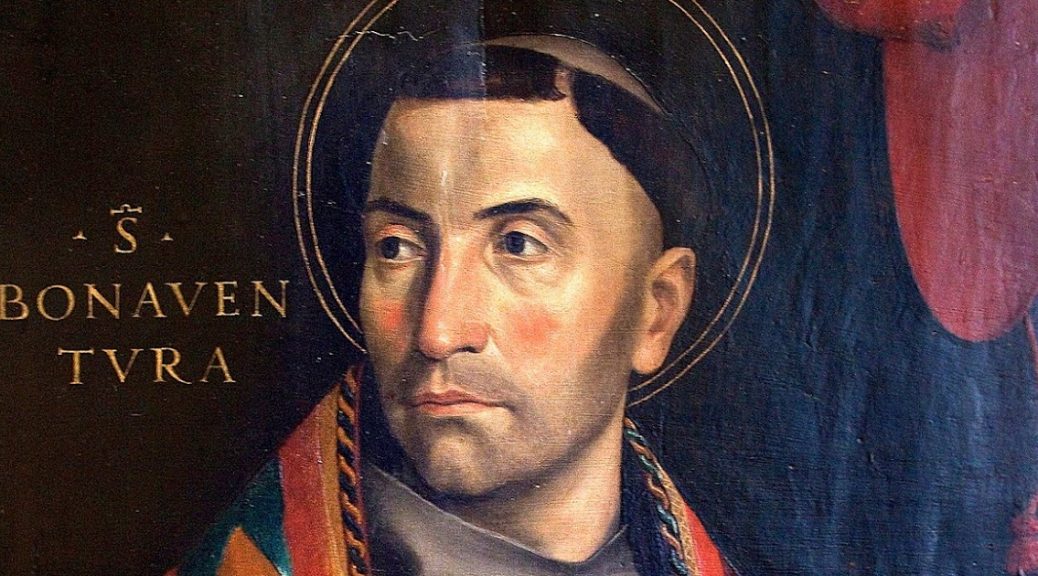

In this paper I look at the spiritual theology of the 13th-century theologian, St Bonaventure. I suggest that because of the arguments affecting the Franciscan order at the time Bonaventure becomes Minister-General in 1257, his major work of spiritual theology is designed to establish a narrative about the meaning of St Francis’ life that would ensure the long-term future of the Order by allowing for lay participation and more moderate ways of following the Rule. I also suggest Bonaventure’s spiritual theology makes use of the mystical teaching of St Clare which is better suited to a non-itinerant Franciscan lifestyle.

Introduction

It is often observed that St Bonaventure places philosophical and theological structure on the lived spirituality of Francis of Assisi – perhaps some modern Franciscans wonder whether that was such a good thing! In this talk however I want to suggest that it is entirely a good thing, because Bonaventure provides a vital bridge between the early Franciscan radical performative reenactment of the Sermon on the Mount and a lived spirituality accessible to generations of non-itinerant and lay tertiaries.

As an academic theologian Bonaventure must have seemed to many an odd choice as the seventh Minister-General of the Franciscan Order in 1257 – though he had an unimpeachable reputation for zeal and holiness. Brilliant and pious while theologically conservative, Bonaventure was thrust into the leadership in the middle of a fierce debate over the figure of Francis himself, interpretation of his Rule of Life and the possibility of lay participation in the Order.

By mid-13th century the Franciscans had grown beyond all expectation – but seemed about to implode. After Francis’ death in 1226 what had begun as an improvised way of life for his small group of friends had morphed into an international order with thousands of friars, creating massive administrative problems and institutional needs for education and formation. At the same time, Francis’ legacy was hotly contested. The so-called Protospirituals, furious at what they saw as the lax disregard of Francis’ teaching on poverty, latched on to the sensationalist 12th-century apocalyptic vision of Joachim of Fiore to declare Francis the angelic harbinger of a great cosmic conflict, setting aside both Old and New Testaments and ushering in the end of time. Bonaventure’s immediate predecessor, John of Parma, had resigned in disgrace due to his own association with the hotheads.

Bonaventure soon proved himself an able peacemaker. Researching his life of Francis in the year he became Minister-General, Bonaventure visited one of Francis’ original companions, Brother Giles, who asked him suspiciously, ‘Can a simple person love God as much as a learned one?’ ‘Even more so than a master of theology’, Bonaventure responded diplomatically – and in his Life of Francis notes that Giles himself while simplex et ignota (simple and unlearned) ‘lived among people more like an angel than a human being’.

Nevertheless, Bonaventure had a fight on his hands to establish a narrative about Francis that could provide a long-term future for the Order as it continued to grow apart from the radical itinerant lifestyle of its founders. I suggest that an integral part of Bonaventure’s response to the problem is to be found in his works of spiritual theology penned over the first two years following his installation as Minister-General. I will make this argument, firstly, by thinking about the general shape of Bonaventure’s spiritual theology, which marries the time-honoured three-fold neo-Platonic way of ascent pioneered by the 5th century Dionysius with new and distinctly Franciscan thinking. I will then turn to a closer examination of Bonaventure’s major work, the Itinerarium Mentis in Deum, or the Soul’s Journey to God, to show how Bonaventure constructs a template for Franciscan spirituality from his interpretation of Francis’ vision on Mt Alverna. Finally, I will suggest how Bonaventure derives his novel elements from Clare of Assisi via his contact with Brother Leo.

The Triple Way

We live in remarkable times. For four dollars you can buy on Kindle and read on your smartphone Bonaventure’s entire Mystical Opuscula , the three works that form the essence of his spiritual theology: the Lignam Vitae (Tree of Life) that anticipates St Ignatius’ way of meditating on the life of Christ in Scripture by four centuries; de Triplica Via (Threefold Way) which insists that love remains even when the intellect is plunged into the darkness of unknowing and that the apotheosis of love is the Crucified Christ; and the Itinerarium Mentis in Deum, (Mind’s Journey into God) which is both a pilgrim’s progress through the whole of the created order into identification with the Crucified One and simultaneously a reinterpretation of Francis’ vision on Mt Alverna as a template for contemplation. All three of these works were written between 1259 and 1260.

Firstly a couple of words about the Triple Way, the last of these works and a practical primer for novice friars. In this little work Bonaventure builds on the threefold mystical hierarchy first expressed seven centuries earlier by Dionysius. It consists of three ways and three exercises. The ways are the purgative (ie. the way of moral virtue or asceticism), the illuminative and the perfective or unitive – the first way leading to peace, the second to truth and the third to love. The exercises are meditation (eg. lectio divina), prayer and contemplation (confusingly, what the Western spiritual tradition refers to as contemplation is more often referred to as meditation in our own day). In the classical Neoplatonic pattern, the three stages take us first outward, then inward, then upward – away from the love of creatures, purifying the intellect and volition and into the unknowing of divine darkness. Bonaventure, however, following the love mysticism of the 12th century Hugh of St Victor, reinterprets the drily intellectual Dionysian ‘unknowing’ (apophasis) as the love that alone can persist when knowledge is extinguished, and adds a twist by using the erotic imagery of the Song of Songs to build up a theme of loving desire between the soul as a bride and its divine Spouse. Finally, in the Triple Way, Bonaventure makes another move that neither Dionysius nor Hugh could have imagined – equating the pinnacle of loving desire with devotion to the cross through which the soul’s identification with Christ is made complete. As I will suggest later this identification with the crucified Christ as the epitome of love joins together the lived experience of St Francis with the mystical teachings of St Clare.

The Journey

When in 1259 he sits down to write his most important work of spiritual theology, the Journey of the Mind into God, Bonaventure also uses the three-fold division of Dionysius but this time he has a very important practical problem to address. In this work, written on Mt Alverna where Francis received the stigmata along with the vision of the six-winged seraph in 1224, Bonaventure sets out to establish Francis’ vision as an eschatological event – which is to say an event that draws the Franciscan Order and through it the whole Church into its apotheosis. Like the Protospirituals, Bonaventure has some sympathy with the apocalyptic theology of Joachim of Fiore – unlike the Protospirituals he sees the significance of Francis not as a cataclysmic event that ushers in the end (ie. finish) of the world but rather an event that ushers in a renewed creation and a reformed doxology. Thus, Bonaventure has both a political purpose of importance to the future of the Franciscan movement and a spiritual purpose to reveal in the life of Francis a pattern of growing conformity to the crucified Christ as a template for an accessible Franciscan spirituality. In the Prologue of the Itinerarium Bonaventure reveals that the journey he is about to describe is a mystical journey into the heart of crucified love, based on Francis’ own journey as icon and exemplar.

In this work, Bonaventure again adopts the Dionysian pattern of outwards, inwards and upwards – it should be said that for Bonaventure these are never stages in the chronological sense that you leave one behind to go on to the next – but doubles each of the stages to correspond with the six wings of the seraph in the form of the crucified Christ. Bonaventure achieves this doubling in a way that emphasises that this is a journey from created being to eternal being, considering the divine presence in each stage as Alpha (initial cause) and Omega (final cause).

The first stage corresponds to what Bonaventure calls the Book of Creation – here, God is known in and through the creatures as Alpha and Omega. By this, Bonaventure means that as we study creation we may see the vestigial fingerprints of the Creator – the Alpha – and we may also see the God made known through the creatures as their final cause or Omega – for Bonaventure this means we reflect on how we are drawn to know God through the deep patterning and order of the external world. If you read this as a 21st century Franciscan expecting a lyrical meditation on the ways God’s beauty is reflected in the natural world and its creatures you might be disappointed – there is definitely scope here for an ecotheological updating of the Journey reflecting on the goodness and beauty of the natural world and its eternal valuation! However in his medieval language we see Bonaventure’s use of the Orthodox notion of theosis – the eternal drawing together of all things in Christ in the service of another Franciscan theme: the vocation of all things for praise.

In the second stage Bonaventure invites us to contemplate our own human soul – again, both as an image of God in its creation – Alpha – and in its eternal vocation of praise and union with God through faith, hope and love reformed by grace – which is the Omega. In this section Bonaventure makes full use of the erotic Spousal imagery from the Song of Songs to depict the soul’s yearning for God. He also describes the soul as a mirror illuminated through scripture and reflecting divine Wisdom.

Thus restored to its proper likeness the soul in the final stage can turn toward God, firstly considering God as Being – the One who gives existence to all things (ie. as Alpha) and then considering God as the Good. Bonaventure uses a number of analogies throughout the Itinerarium – for example that of ascending Jacob’s ladder, then in the fourth chapter the entry into the heavenly Jerusalem before introducing at the end of chapter five the metaphor of the soul as the temple of the Holy Spirit. This metaphor dominates chapters five and six, where Bonaventure tells us we have already entered the atrium and the holy places of the temple but now must enter the Holy of Holies. What follows is the description of a sort of mandala, the Holy of Holies inhabited by twin cherubim gazing at the mercy seat between them, that awesome place in the temple in Jerusalem where God’s presence dwelt as a sort of fecund absence. We are meant, I think, to construct a visual image of this, as we contemplate firstly the cherubim who proclaims the name of God as Being: I am that I am – the Alpha of all creaturely existence – and then turn our inner eye to the second cherub on the other side of the mercy seat who proclaims the name of God as the highest Good. This name of God necessarily requires as to think of God as a loving trinity whose own life is characterised as a flow of self-giving love. Goodness, identified as the procession from Being to Being-For or Being-Towards or even Being-Given – draws all things to their true end or Omega in loving union.

At each stage of the journey the mind is drawn from outer to inner and from beginning to end until finally in the seventh chapter the soul is able to follow the gaze of the cherubim and contemplate the mercy seat. This is the empty place above the altar in the Holiest of Holies filled with the invisible presence of God, in the Itinerarium made shockingly visible in the form of the crucified and lifeless Christ. The journey reaches its culmination (which Bonaventure refers to as a Passover) In the soul’s contemplation of the crucified Christ – at this point God remains unknowable but able to be embraced in love.

In his Life of St Francis (Legenda Maiora) Bonaventure had named Francis as the ‘hierarchical man’, who bearing the marks of the stigmata is be identified with the angel ‘having the seal of the living God’ in the apocalyptic vision of Revelation 7.2. And so the Itinerarium begins with the intention expressed by Bonaventure in the Prologue to understand and retrace the journey of Francis, and ends with an image of Francis’s contemplation and embrace of the Crucified made visible for us in the stigmata. It is here that the intellect enters the darkness of unknowing – but following Francis we are able to so identify in love with the crucified Christ that Bonaventure bids us rest with him in the darkness of the tomb.

For Bonaventure, then, Francis represents a sort of icon for our meditation, a window into Christ who is himself an image of the invisible God. The importance of his project in the Itinerarium is to offer a way of imitatio Francisci that does not involve stripping yourself naked before the bishop, renouncing all possessions and undertaking a lifelong performative re-enactment of the Sermon on the Mount. By mid-13th century the life of Francis had already begun to recede into highly contested and even mythologised history. However, Bonaventure suggests that through contemplating the image of Francis stigmatised we ourselves may see Christ – so Francis is both an example of perfect human union with God and a visible icon for our own journey into the heart of Christ.

Clare’s way

Less obvious is that in this project Bonaventure also interprets the penultimate experience of Francis’ life using the techniques passed down from Clare of Assisi. As has become well known, Clare and her sisters lived a life very different to the mendicant performative imitation of Christ lived by Francis and his companions. Enclosed in community and refusing even to work or beg for alms, Clare’s community practised a poverty possibly even more extreme than that of their brothers. Better recognised now, thanks to writers such as Ilia Delio, is the interior poverty and contemplation focussed on two central images developed in Clare’s letters to Agnes of Hungary: Christ as Spouse and as Mirror. The spousal imagery drawn from the Song of Songs and also found in St Paul’s letters and the early Church Fathers, is beautifully drawn in Clare’s first letter to Agnes in which the embrace of poverty becomes a form of union with the “poor Crucified”. As I noted earlier, this imagery is also central to Bonaventure’s spiritual writing.

In her second and third letters Clare combines the spousal imagery with that of the mirror, inviting Agnes to ‘gaze, consider, contemplate, desiring to imitate your Spouse’. This movement from gazing into the mirror of Christ, to considering, contemplating and imitating becomes a sort of interior journey that functions like Francis and his brothers’ literal, performative representation of Christ’s itinerant life. As Jay Hammond notes, although Clare probably first receives the mirror metaphor from earlier Cistercian sources her development in the letters to Agnes is unique and personal because she lacks access to a library in her monastery. In her fourth and final letter to Agnes, Clare provides a deeper reflection on the journey of contemplation, describing the mirror of Christ as giving access to the entire mission of the Incarnate Word as the radical poverty of God giving Godself away in love. Clare in this letter invites Agnes to transform herself into the image by gazing into the mirror which is Christ, in whom we also see the image of ourselves as we are created to be.

In the Itinerarium, Bonaventure notes that his work is based on conversations he had with Brother Leo who was with Francis when he received his vision. There is no record of Bonaventure having personally met Clare, who died in 1253. However, in a letter to the Abbess of the Monastery of St Clare in Assisi written in the same year as he composed the Itinerarium (1259), Bonaventure writes that he has also received news of the sisters from Leo. Using similar terminology to that of Clare’s letters to Agnes Bonaventure in this letter enjoins the Abbess to contemplate the mirror of Christ. The case for Bonaventure having been made aware of Clare’s contemplative imagery through Leo thus seems fairly strong.

In the Itinerarium, Bonaventure integrates the theme of the mirror with that of Francis’ beatific vision, writing that the wings of the Seraph are mirrors through which we can gaze on Christ. By this he refers to the mirrors of creation and of the human soul which reflect their Creator. He writes that these mirrors reflect the light of Christ so that to gaze at creation is to recognise the presence of Christ in all things – though in the Prologue he also cautions that these mirrors must be cleaned and polished before we can see clearly in them! Ultimately in Bonaventure’s vision it is the Crucified Christ himself who is the perfect mirror of God, and the stigmatised Francis who becomes for us a mirror of Christ.

Conclusion

Bonaventure, as one commentator notes, is both more and less than Francis! He leaves us wanting more of the immediacy and freshness of Francis’ perception of reality – while Francis himself maybe leaves us wanting something more suitable for everyday practicality! Bonaventure is primarily writing for the needs of his own mid-13th century community trying to find a settled narrative and a way forward from self-defeating disputation. However in the Itinerarium he also provides a road-map for a Franciscan spirituality that by drawing on the mature spirituality of both Francis and Clare is able to be emulated by future generations.

*** +++ ***

References

Ables, Travis. ‘The Apocalyptic Figure of Francis’s Stigmatized Body: The Politics of Scripture in Bonaventure’s Meditative Treatises’. In Reading Scripture as a Political Act, edited by Daniel McClain and Matthew Tapie. Fortress, 2015. 25/6/2021.

Bonaventure. Itinerarium Mentis in Deum. Edited by Stephen Brown. Translated by Philotheus Boehner. Works of Saint Bonaventure, Translation from the Latin Text of the Quaracchi Ed. Saint Bonaventure, NY: The Franciscan Institute, 1998.

———. Mystical Opuscula. Translated by José Oscar de Vinck. Kindle edn. The Works of Saint Bonaventure: Cardinal, Seraphic Doctor and Saint, vol. 1. Edinburgh: CrossReach Publications, 2017.

———. ‘The Life of St Francis (Legenda Maior)’. In Bonaventure: The Soul’s Journey into God/The Tree of Life/The Life of St Francis, translated by Ewert Cousins, 179–327. The Classics of Western Spirituality. New York, NY: Paulist Press, 1978.

Cousins, Ewert. Bonaventure and the Coincidence of Opposites. Chicago, IL: Franciscan Herald Press, 1978.

Delio, Ilia. Clare of Assisi: A Heart Full of Love. Cincinnati, OH: St. Anthony Messenger Press, 2007.

———. Franciscan Prayer. Kindle. Cincinnati, Ohio: St. Anthony Messenger Press, 2004.

Hammond, Jay M. ‘Clare’s Influence on Bonaventure?’ Franciscan Studies 62 (2004): 101–17.

Hayes, Zachary. Bonaventure: Mystical Writings. New York, NY: Crossroad Publishing Company, 1999.

Hughes, Kevin L. ‘Francis, Clare, and Bonaventure’. In The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Christian Mysticism, edited by Julia Lamm, 282–96, 2012. www.academia.edu.

McColman, Carl. The Big Book of Christian Mysticism: The Essential Guide to Contemplative Spirituality. Kindle edn. Charlottesville, VA: Hampton Roads Pub. Co, 2010.